Perrotin Dubai Opens Xiyao Wang’s First Middle Eastern Solo Exhibition, The Drifting Island

Dubai — Perrotin Dubai has opened The Drifting Island, a solo exhibition by Berlin-based Chinese artist Xiyao Wang, on view from January 14 through February 28. The exhibition marks Wang’s first solo presentation in the Middle East.

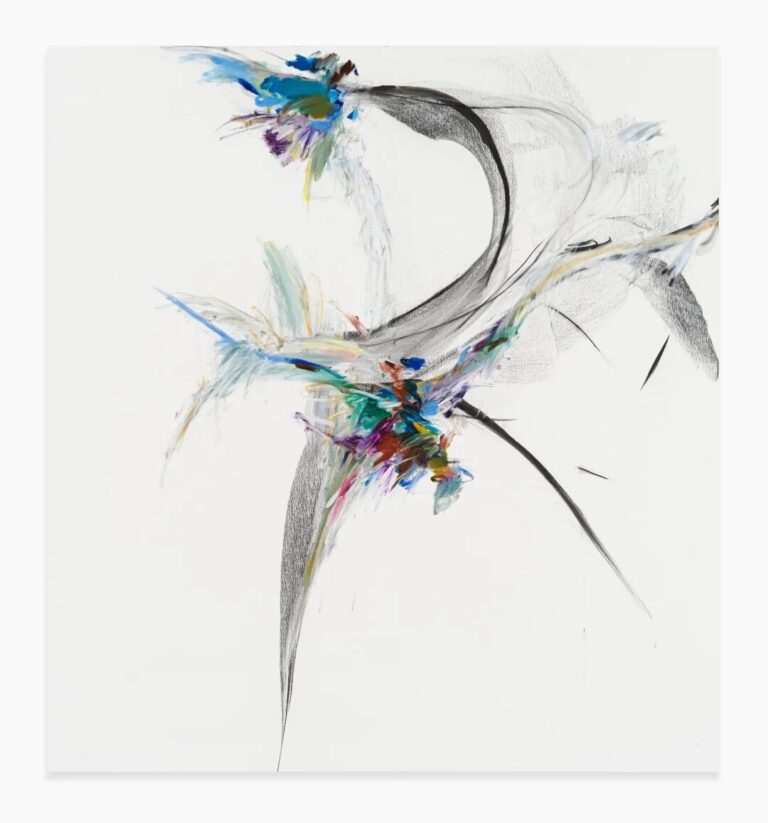

The exhibition brings together a new body of paintings that examine movement, rhythm, and embodied perception. Rather than indexically representing motion directly, Wang focuses on the sensation of movement itself—its fluidity, tempo, and transience. Time, in these works, is understood as continuously shifting: drifting like a river, passing like clouds across a landscape, or unfolding through the movement of the artist’s body in the studio.

In recent years, Wang has increasingly pared down her visual language, reducing both composition and color in order to concentrate on what she considers the most fundamental element of painting: the line. This process of reduction, however, is accompanied by an intensified attention to precision. Her restrained charcoal lines on white canvas recall the discipline of calligraphy, while also reflecting her engagement with German Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism, traditions she encountered after relocating to Germany for her artistic training.

Color enters the works only at later stages and is used sparingly, serving to sharpen focus rather than dominate the surface. White space plays a central role, functioning not as absence but as a deliberate pause—allowing for rhythm, breath, and resonance within the composition.

Wang’s practice is shaped by a range of bodily disciplines, including yoga, dance, meditation, and her long-term study of the guqin, a traditional Chinese string instrument. These practices inform her sensitivity to tempo and duration, translating into varying intensities of line and gesture. Slow, deliberate marks carry a different energy from those executed with speed, with each gesture registering a distinct rhythm and moment of concentration.

Positioned between movement and stillness, Wang’s paintings do not seek to capture motion itself, but rather to preserve its trace—a fleeting state, a flicker of consciousness. Viewers are encouraged to slow down when encountering the works, engaging with their quiet rhythms and entering a reflective space between inner experience and outward perception.

Artist in Conversation

The exhibition is accompanied by excerpts from a conversation between Wang and curator and critic Hou Hanru, recorded in Berlin in September 2024.

Hou Hanru: Could you describe your painting process? How do your works unfold in terms of line, movement, composition, and color? Do your lived experiences and memories of reading manifest concretely, or do they emerge abstractly and spontaneously? Do you work with a predetermined plan?

Xiyao Wang: For me, the search for the most “accurate” expression is paramount. Sometimes, figurative representation feels insufficient because it can only render a specific image. What I aim to express is a fragment of time, not just a fragment of space. When I attempt to articulate life experiences or literary memories, the sensations themselves—be it temperature, color, form, or the shifting states of existence—are difficult to literalize. They often exist in the liminal space between the figurative and the non-figurative.

The most “accurate” moment is the one you can truly manifest in the present—much like the click of a camera shutter. The world looks a certain way in that instant, but even that isn’t its “true” entirety. You’ve only captured a fragment of the world, a fleeting moment within the continuum of time. That is the sensation I strive for when I paint: the “here and now,” the point where I am moved, and how that resonance is transmitted.

Hou Hanru: This process involves a great deal of movement and gesture. You’ve also mentioned that music is a significant influence.

Xiyao Wang: Yes, because it touches on a crucial element: the passage of time. The perception of time is a vital factor in my work. Movement, music, and bodily sensation all unfold along a temporal axis; these experiences have reshaped my understanding of time as a primary structural element in painting.

Wang also points to historical precedents, noting that time has long been embedded in visual traditions such as classical Chinese handscroll painting, where viewing unfolds sequentially, as well as in Western medieval compositions that guide the eye through narrative space. In her own practice, however, time is not a secondary effect but the central concern.

All text and images above are from the artist.